This post was originally posted in May, 2015 on the old site.

This post was originally posted in May, 2015 on the old site.There’s a book that I used to read to my kids that’s called the Quiltmaker’s Gift. It tells the story of a magical old woman who made beautiful quilts (all by herself) and gave them to the poor. “ ‘I give my quilts to those who are poor or homeless,’ she told all who knocked on her door. ‘They are not for the rich.’ ” Well, that’s all fine and good, but what if we were to tell you that for the price that quilt would get on auction, we could support 150 homeless people for a year and send two aid workers to Nepal? Would you sell it now?

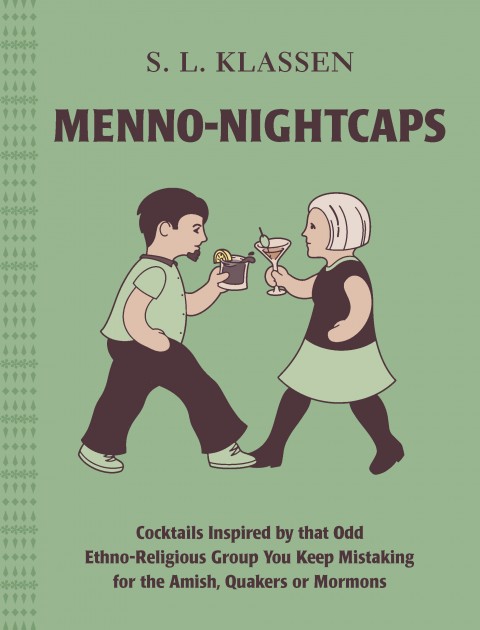

Welcome to the annual MCC relief sale quilt auction. This is ground zero in North American Mennodom. We’ve been holding relief sales since 1957 (we don’t sell relief there) and quilts have held pride of place there just as long.

But never mind all that. Come to a Mennonite relief sale and you will find quilts and dozens to hundreds of people who will insist that quilts are a core part of our socio-religious-cultural identity; you can even find quilts stitching their way into our theology.

If you know me at all, or have read more than a few sentences of this blog, you won’t be surprised that I have never been drawn to the great female Mennonite cultural event known as the quilting bee. Unlike the magical quiltmaker of the children’s story, the quilts sold on auction and claimed as icons of our faith and life, are not traditionally made by solitary old women who happily stitch away with a cup of blackberry tea in one hand and birdsong chirruping away outside the window. No siree. These quilts are a collective effort, representing hundreds of hours of piecing together scraps of cloth into a pattern, painstaking needlework by a whole church of women with backs bent over a large frame, fingers calloused and cut from thread, and eyes strained from detailed precision all working together in a dank Church basement.

This is not the kind of place for a Drunken Mennonite.

And yet. Back in the days before all my drunkenness, there was a brief period in my tweendom when my dear grandmother (Oma, to me) tried to lure me down the path of quiltmaking. Oma was not a born quilter, having come from Russia instead of Pennsylvania, but like so many other Russian Mennonites who came to North America, once here she did her best to assimilate into the dominant North American Mennonite culture. Yes, by learning to quilt.

And so it happened that one fine day when I was blissfully ambling my way through middle childhood, my mother and her mother came to me with the brilliant plan that the three of us would make a quilt. We decided on autumnal colours in a classic log cabin pattern, that nice beginner’s pattern that consists of hundreds of different sizes of rectangles of fabric spiraling out from a series of central squares like drunks staggering surprisingly politely out of bars at closing time. It’s kaleidoscopic without being disorderly. How great is that?

We made a demo square to make sure that it would work when sewn together. And when we looked at the full square we completed, we all three of us smiled and declared that it was good. Then, we took a rest.

One can learn project management anywhere. Getting past the guilt of unfinished business is a special skill.

At any rate, a couple of years after we had completely given up on the quilt project, I turned the demo square into a cushion for a home economics project and that cushion graced my couch for many years until my cat pissed on it and I trashed it, thereby eliminating all physical evidence of my brief foray into the life of the quiltmaker.

And that’s that. Let’s have a drink. In researching this post, I came across a book of quilt patterns based on classic cocktails (and people think that I write for a niche audience!). But I wanted it the other way around and so I put my own twist on the Log Cabin cocktail and am calling it the Twisted Log Cabin, which is its own quilt pattern that kinda looks like a drunken version of the original. And it’s such a great cocktail name that I couldn’t pass it up. It’s got autumnal flavours, just like the colours of my almost quilt. That might not feel right for May, but it’s not heavy like a winter drink and apples are good all year round. If we toss a few dashes of rhubarb bitters in there, it’ll bring us into spring and help us remember that this drink is as Mennonite as a nice piece of platz. Or shoofly pie, or whatever you like.

The Twisted Log Cabin

2 oz Canadian rye whiskey

1 oz Calvados

1/2 oz Lemon juice

1/2 oz Maple syrup

1 oz Sparkling water

2 dashes of Rhubarb bitters

- Stir all ingredients but the sparkling water together in a mixing glass.

- Add sparkling water.

- Pour over ice in short serving glass

- Garnish with a slice of apple that you have painstakingly cut into just the right size of rectangle. Or not.

Do not serve this drink at a quilting bee but do pull it out whenever you need a tasty libation to help you forget the boxes of fabric in your closet and mourn the hours you lost cutting fabric into squares or rectangles or circles or hexagons or triangles or diamonds. It’s true. You’ll never get those hours back.

Hilarious! So what happened to the box of cut fabric? Could it still be resurrected for this May’s 50th Mennonite Relief Sale in New Hamburg?? And the cocktail sounds delic.!

I expect the box of cut fabric went to the thrift shop at some point and, thus, may already have worked its way into someone else’s quilts. Or, it’s sitting in someone else’s closet now making them feel guilty…