This post first published in July, 2015 under a different title (But am I a real Mennonite?). In addition to changing the title, I have also corrected a typo.

This post first published in July, 2015 under a different title (But am I a real Mennonite?). In addition to changing the title, I have also corrected a typo.Every now and then a blog post gets derailed.

This one, for instance, was intended to be a little glossary of Mennonite insider language, a guide for the Mennocurious who read this blog but don’t have a clue what I’m talking about. Just in case there are people like that. It was to be set up like a handy dandy series of dictionary entries. It was going to be helpful and amusing both. Doesn’t that sound nice?

Well, forget it. I tried. I tried valiantly to come up with a list of terms and definitions. But, sadly, I could never get past the first entry without finding myself in that pit of despair known to us in Mennoland as the Great Mennonite Identity Crisis.* That’s right, I probed too deeply into the question: What does it mean to be a Mennonite?

It’s not that no voices offered up definitions of Mennonite. Oh, no. There were answers to that question. So many voices with so many answers. And such long answers. Everyone who ever dated, met or saw a Mennonite across a crowded room seems to have their own notion about who and what we are. And those who haven’t, think we are meninists. Um, no. We’re not.

Unsurprisingly, Twitter gives the briefest of answers, telling me repeatedly that Mennonites are like Amish except we use electricity. This isn’t true. There are Mennonites who don’t use electricity and there are Mennonites who have little but shared Anabaptist roots with the Amish. And in some places, the Amish and the Mennonite have settled their differences, joined Churches and even intermarried. It’s complicated.

More serious answers tend to focus on what people in Mennonite Churches believe. Which would be fine if we could assume that people who self-define as Mennonite actually go to Church and believe what the Church says we believe. Some do. Of those who attend Mennonite Churches, the vast majority believe in following the teachings of Jesus as expressed in the Bible. Beyond that, I’m not sure it’s fair to generalize. Some refuse the term Protestant though there’s no denying that we sprang out of the same primordial religious ooze as all the other Churches and Churchlets that found their origins in the Protestant Reformation. Most of us believe in peace and nonviolence, and most believe in the value of community. Whatever the particular tenets of faith, Mennonites tend to say that the way of living is an expression of faith and more important than assertions of belief. We like to think we are the Cordelias of the Radical Reformation.

But there are problems with even that caveat-ridden definition. Technically, one becomes a Mennonite by getting baptized as an adult in a Mennonite Church. Mennonites form a voluntary faith community. Baptism follows some sort of catechism or faith teaching and some way of expressing one’s agreement with the tenets of faith in that particular congregation. That means that simply believing in the tenets of faith and living a life consistent with them is not enough to be fully Mennonite. Nor is Sunday service attendance. Children get a free pass for awhile but we all know, as we get older and older while evading baptismal waters, that we can also evade the label of Mennonite whenever we choose because if we didn’t join, then we’re not part of the club. And if you ask someone about their identity as a Mennonite and it is someone who maybe walks like a Mennonite and talks like a Mennonite but hasn’t been baptized like a Mennonite, they may pause a disarmingly long time before answering. Now you know why.

That’s not the only problem. We also have our own little ethnicity problem. Mennonites have historically been a people of diaspora, moving originally from the Netherlands, Switzerland and South Germany to anywhere in the world that would take them and let them live in communities with varying degrees of isolation from the cultures around them. After a few hundred years of this, we developed a group identity. No, actually, we developed a bunch of group identities — one for every group of Mennonites that lived for any length of time in any particular corner of the world. Ethnic Mennonites in southern Manitoba think that being a Mennonite means eating schmauntfat and spitting out the shells of sunflower seeds. Ethnic Mennonites from Pennsylvania think it means eating shoofly pie and making wooden furniture that looks much like any other wooden furniture. Ethnic Mennonites from Mexico think of tacos and a minimalist education as intrinsic parts of their ethnic identity. And on, and on. Some people say we should eliminate any ties to ethnicity, showing that Mennos, too, can bring a discussion to reductio ad Hitlerum. But I live in a country that pays lip service to the idea of multi-culturalism and if my heritage has almost 500 years of Mennonite peculiarities with borrowed foods and nasty patterns of social control, it may not be much but it is still my culture, even if 15 other groups also claim it and define it differently.

It probably goes without saying that some ethnic Mennonites also attend Mennonite Churches, believe the shared tenets of faith, live lives consistent with their beliefs and have been baptized into their Churches. Other ethnic Mennonites do some of those things and not others. And others do none of them. And, of course, a lot of people who do not have Mennonites in their ancestry going back at least five generations also attend Mennonite Church, believe the shared tenets of faith, etc. etc. Some of these non-ethnic Mennonites like to call themselves “new” Mennonites. This probably gets tired after a couple of generations.

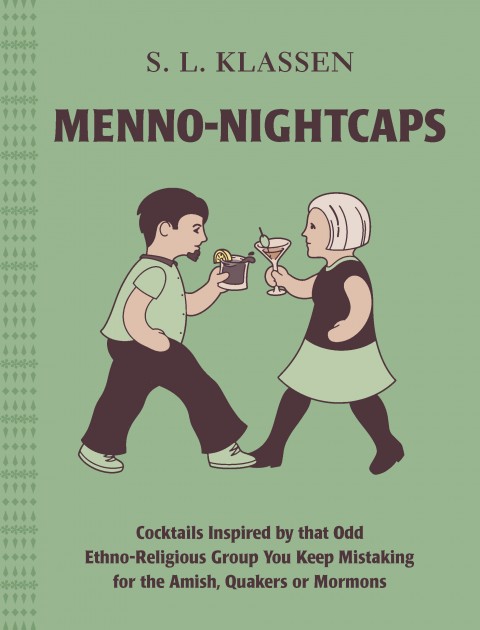

And I’m getting the sense that this post, itself, is getting pretty tired. Anyone who came here actually hoping for a clear answer to the burning questions about Mennonite identity was probably ready for a drink a good two paragraphs ago. I have it on good authority that non-Mennonites often find their first encounter with a Mennonite somewhat exhausting. Not because we are so full of energy, but because we are so full of long explanations about what we (as Mennonites) are and are not. No blog post will help with that. But there’s a cocktail.

Long Explanation Iced Tea

Someone at the Drunken Menno Virtual Cocktail Party (if you missed it, keep your eyes peeled; I’ll have another one some day) was drinking Long Island Iced Tea. I’d forgotten all about it and was grateful for the reminder. R emember to use an artisanal, local and/or fair trade cola.

emember to use an artisanal, local and/or fair trade cola.

1 oz gin

1 oz white rum

1 oz tequila

1 oz vodka

1 oz lemon juice

2 oz cola

1 lemon wedge and a handful of raspberries to garnish.

- Fill a tall glass 3/4 full of ice.

- Add all ingredients except the cola and the garnish

- Stir well.

- Add cola to fill the glass.

- Garnish with lemon and raspberries. Though there’s nothing particularly Mennonite in the ingredients of this drink, I’ve never known a Mennonite who didn’t like raspberries. And, really, haven’t you had enough cocktails with rhubarb bitters?

*Yes, I just made up the term “The Great Mennonite Identity Crisis.” That doesn’t mean it isn’t real.

I just got done posting my own blog regarding what is a real Mennonite…and was checking online for anything that might run parallel with my scenario and my search led me to where you wrote ; “But, sadly, I could never get past the first entry without finding myself in that pit of despair known to us in Mennoland as the Great Mennonite Identity Crisis.* That’s right, I probed too deeply into the question: What does it mean to be a Mennonite?”

Ms. Klassen I can deeply appreciate where you were coming from;

Best Regards;

Delmer B. Martin

RR#4Elmira ON