Once upon a time, a group of Ontario Low-German speaking Mennonites with ties to Mexico broke off from their home Church denomination and decided to start a new sub-sect, calling themselves The Edenthaler Mennonites.

Once upon a time, a group of Ontario Low-German speaking Mennonites with ties to Mexico broke off from their home Church denomination and decided to start a new sub-sect, calling themselves The Edenthaler Mennonites.

All this happens before the action opens in the first episode of CBC’s Pure but it is crucial for all that follows.

It’s a fair assumption that the Edenthalers were once Old Colony Mennonites since the news stories that inspired this fiction were about Old Colony Mennonites. That a schism would occur is not all that implausible, since our tendency to schism is a pretty universal trait. I am not familiar enough with the Old Colony Mennonites to know why they might have schismed. Perhaps they thought the Old Colony Church was too worldly; perhaps they wanted stronger Church discipline.

But that’s not important. You know, schisms happen.

As I pointed out last time and has been noted by others, this particularly curious group decided to set up a new community almost but not quite like the Old Order Mennonites. This is unprecedented and unlikely but, admittedly, it’s not impossible. Maybe the Old Colony schismatics fell in love with the Old Order way of life when members of the Old Order offered their assistance in setting up independent schools (they really did help with schooling). Or maybe the schismatics just read a bunch of Beverly Lewis books.

“But, why?” all us Mennos on social media asked. “Why not just do a story set among the actual Old Colony Mennonites?”

We haven’t had an answer from the makers of the series on this, yet. Possibly because we haven’t actually asked them.

As this is billed as serious TV, however, I like to think that the choices made about bonnets and buggies were made in order to convey something to the largely non-Mennonite viewing audience – something more and deeper than ‘this is what Mennonites look like.’

Here’s my guess.

The first episode featured a lot of boundary maintenance.

Every community – from the high school clique to the nation-state – spends time and effort in deciding and enforcing the rules about who is in the community and who is not. Those of us seeking to make inclusive communities wrestle with the contradictions involved on a regular basis. On the screen, plain-dressing Mennonites visually punctuate the distinction between insiders and outsiders with great effect.

At first blush, the line between insider and outsider is clear and sharp. The scenes with the dissolute detective contrast with the orderly Church scene and the idyll of Funk’s farmyard. The clothes of the school children set them apart from their peers. The simple black and white of the Amish clothing suggests absolute clarity. The German and that strange accent all suggest a sharp “otherness” from the people referred to here as auslanders (I have not heard this term used for non-Mennos before but a brand new sect can do what it wants, and calling them all englanders would probably confuse the englander audience).

It wasn’t just about bonnets and buggies. The dialogue had a lot of boundary talk as well (much more than you would actually hear among Mennonites). Bringing a missing child to the police is not “our way;” smuggling and hiring hit men is not “our way;” the rules are not the pastor’s alone but are “ours;” the teenaged daughter should watch her tongue lest she “sound like one of them.” And, of course, the kicker comes when the pastor contradicts the cop who called the drug smugglers “your people.”

The second episode eased up a bit on all the boundary talk. Which is a pretty big relief – I think we’ve had enough.

But the boundaries aren’t clear in any community. It’s not clear for a nation and it’s not clear for a Mennonite community. The clothing choices mark some distinctions here – people on the fringes of the community (people like Voss, and the family killed in the first 30 seconds of the first episode) dress a bit more Old Colony than the pastor’s family and the Bishop. Maybe this is because they are more closely connected to Mexico and the fashions of the Mennonites there, or maybe it is to indicate that they are in that dangerous place – on the edges of a community, neither “in” nor “out.”

In the second episode, various people try to cross boundaries – the cop, the daughter, the pastor – without much success. I predict that they may improve on their transgressing of boundaries as the series continues. But we’ll have to see.

Popular culture often valorizes the outsider, lionizing outlaws and sympathizing with people on the edge of their communities. I suspect that the makers of Pure expected that Mennonites would like the show because they refrained from making heroes out of the people who flaunt the community’s norms. The Mennonites who are loyal to their faith and community values are – at least so far – portrayed sympathetically. This isn’t a Footloose kind of series that lampoons the Mennonites as small-minded hicks.

So there’s that.

I don’t imagine that they realized we would get so hot and bothered about the clothes and means of transportation.

From the first two episodes, it is hard to say whether we are in for a nuanced lesson on community and the boundaries that groups establish around themselves. I don’t know if we can writ the story large into a tale of nations struggling over stateless criminals, or writ it small into a tale of office politics where informal power exists in the fuzzy zones of personal interaction.

From a Mennonite perspective, the series shows people dressed as Old Order Mennonites as mostly good and godly, and those dressed as Old Colony Mexican Mennonites as the dangerous fringe on the Mennonite gemeinschaft. Yeah. That’s a problem. There’s also a general whiff of deviance around the Mennonite women who dress like the englander – the preacher’s daughter and the cop’s prostitute – crossing boundaries in a different (sexier) direction. That, too, I would say, is a problem.

The threads that tie together the whole patchwork of Mennonite communities in Ontario are, truth be told, pretty weak ones. There are boundaries between us that were created either when the first schisms happened or simply as cultures evolved over centuries of migration. We cross those boundaries ever so rarely – at the annual MCC relief sale, or at the Credit Union formerly known as Mennonite. Sometimes some of us will sing together. Some people do business across the boundaries, and there are scholars who have made it their business to cross the boundaries and learn about the people there.

For the most part, our boundaries work like good fences. We don’t see ourselves as rival gangs or competitors for souls. We also don’t see ourselves on a hierarchy or continuum of “Mennoniteness.” We most certainly have stories in our history of one group declaring another ungodly, worldly, backward, or simply wrong. As a general rule, I think we try not to do that anymore.

But we’re also not such a happy family that we don’t mind when people just mix us up with each other. We know a thing or two about keeping up boundaries between groups of seemingly very similar people. Sometimes for good and sometimes for ill.

These are things you won’t see on TV.

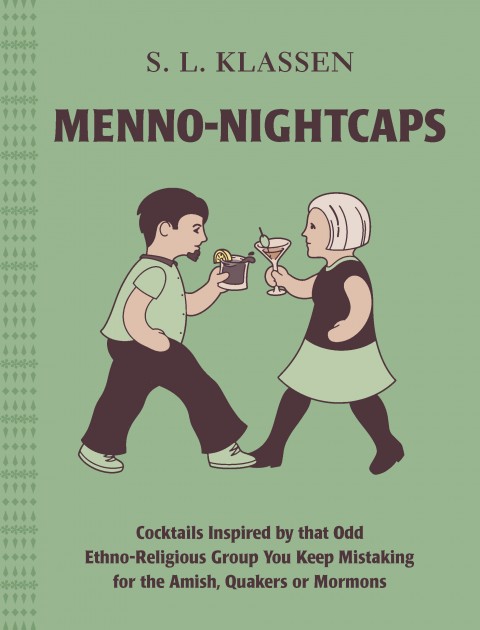

I haven’t got a new cocktail this week. Do you honestly need another cocktail to go with this TV show?

You probably still have some ginger beer left from last time. Just make yourself another Mennonite Mule and be done with it. I’ll have another cocktail recipe next time.

You left the Mennonite schools off your list of places were people cross boundaries. Perhaps more in Ontario than other places, based from what I remember of Mennonite High School choir festivals.

I worked as the advertising mgr for a Cdn mfgr with Mennonite ownership. in the early 2000s, as we stepped up marketing to US regions, we hired a US ad agency. They (New Yorkers and PA folks) became fascinated by all things Mennonite. There appeared to be a Menno “brand” that was widely perceived and in fact greatly influenced by Harrison Ford and Kelly McGillis in “Witness” (1985). Focus groups and other marcom analysis suggested to us then – no surprise – that faith, honesty, simplicity, honour & perseverance were touchstones for our target audience (wealthy US homeowners) when they were asked to relate their sense of “Mennonite”. The depth of the perception did not go much beyond that and a few icons – buggies & bonnets. My guess would be that the Witness-Hollywood-Mennoporn viewpoint still resonates in the US, but less so in Canada where a higher % of “Englanders” have grown to know Mennonites first hand. CBC may have gone lowest common denominator in order to hit that sweetspot POV prevalent in the US and not unacceptable to Cdn viewers, even if a few of them would discern it as “lang nicht kloa”.

P.S. – maybe the buggy followed the horse? In 1974, my Intro Geography prof at UVIC in BC proclaimed what was essentially the “Witness caricature” to our lecture theatre full of absorbent sponges. Until, that is, a brave, bonnet-less young lady from Abbotsford stood up and LOWERED THE BOOM on that Liverpudlian misinformation purveyor. She got a standing O from me – a fresh ruboaba stalk from Manitoba.

Did I just miss it each week or was episode 4 the first time they included the disclaimer the show is not based on actual facts etc. Good thing – I was beginning to believe that maybe this all really did happened!! I would like to review the bullet trajectory from the barn to the fallen drug dealers – I think the guys in the barn could plausibly argue they were not the shooters.

I didn’t notice either. I did notice that the header to the CBC viewer online now identifies the group as Old Order. Pretty sure that’s new.

I tried to bribe my way in with the promise of free buns & cheese. To no avail. Makes me believe no true Mennonites are in the executive suite.