When I was a grad student studying history, stories used to go around about rich Americans who would pay people like us to dig up their family histories. Though it sounded like a cash cow, the stories usually ended with having to deal with the ire of people discovering that their ancestors were neither luminaries of the Enlightenment, pirates of the Caribbean, nor bejewelled nobility, but merely shopkeepers, labourers or petty criminals.

When I was a grad student studying history, stories used to go around about rich Americans who would pay people like us to dig up their family histories. Though it sounded like a cash cow, the stories usually ended with having to deal with the ire of people discovering that their ancestors were neither luminaries of the Enlightenment, pirates of the Caribbean, nor bejewelled nobility, but merely shopkeepers, labourers or petty criminals.

Believing ourselves wise in the ways of history, we graduate students laughed at the rich Americans’ disillusionment. What fools they were to imagine their antecedents as part of history’s one percent.

As a general rule, Mennonites don’t imagine that our ancestors were the aristocracy of old. But Mennonites, too, can become disillusioned if we start exploring our past. Our illusions are a little different from those of the proverbial rich Americans. No imagined princelings in our heritage, we Mennos tend instead to imagine our ancestors as simply good, peace-loving farmers untouched by the vicissitudes of history and unjustly persecuted for our faith.

It can come as a blow to learn otherwise.

This disillusionment is not an uncommon phenomenon – I think of it as something like a coming of age – but it is rare enough that every Mennonite who begins reading up on the historical scholarship feels the shock of discovery as if they alone among Mennos have learned to see past the platitudes to the Truth. Sometimes I think there should be a support group for all the Mennos and post-Mennos who start poking around the past. So that those of us who have been there can comfort the newly disillusioned and let them know that it’ll be ok.

I feel like Ed Wall needs that kind of comfort.

Earlier this year, Wall published a blog that put on display his own disillusionment with Mennonites even as it tells his father’s personal history in the context of Mennonite and world history. Armed with his father’s journals and (presumably) access to an academic library, Wall set out to understand and explain his father, a Mennonite man who immigrated to Canada in his thirties after the second world war. It’s an ambitious project because he set out to understand his father in “a long view,” stating,

If you take the short view, you might not understand how Gerhard ended up working for the Nazis, but if you take the long view, a pattern begins to develop.

Actually, I’d say that there are several patterns that one could see upon taking the long view. This is why histories continue to be written – each time we look, we see different patterns depending upon the lenses we look through and the traces of the past that we look at. And also, of course, depending upon the reasons one is looking to the past in the first place.

The pattern that Wall sees is one of recurring hypocrisy, arrogance and greed among the Mennonites. It’s a cherry-picked history to be sure, but so is the more common narrative. Wall just prefers sour cherries to sweet. I won’t argue with that – sour cherries make better pie. And also fruit verenejke.

None of these accusations will come as a surprise to the disillusioned Mennonites among my readership. Still, Wall is so extensive in his listing of Menno misdeeds that even the most disillusioned might find something in his 64 blog posts that is new to them. Not that he is exhaustive — Wall only occasionally wanders away from the branch of Mennonites that related to his father and his father’s ancestry and leaves out a lot of silliness.

But I think that’s fine. It just means that there is still plenty of material out there for others to highlight should they wish to add their own disillusioned voice to the chorus.

To a certain extent, the story Wall tells is yet another incarnation of one of the morality tales that we Mennonites weave of our history. His is a story of a bad – or at least befuddled – people met with judgement. In this version, our badness is mostly economic injustice. I looked in vain for more than passing references to our restrictive theology, many religious divisions and/or patriarchal institutions. Those are part of the story, too, and quite possibly just as relevant.

Still, Wall’s account stands out for its efforts to connect the personal — a sympathetic tale of the author’s father, Gerhard — with a harsh indictment of his culture. As such, Gerhard’s successes are always a little bittersweet as they came from luck and privilege not through merit, the administration of justice or even the grace of God. Would that more people looked at their ancestors’ success through such a lens.

Like a true unsleeping evangelist, Wall interrupts his own narrative and devotes blog post #62 to a rant, calling on all Mennonites to repent from our wicked ways – most particularly the wickedness of sugarcoating the past and blaming all our troubles on others.

I hang out with enough disillusioned Mennonites to have heard this call over and over again.

I admit that I am growing weary of it.

I agree that it would be nice if Mennonites could drop the sanitized version of our history. For one, it’s a really boring narrative that leaves out a lot of the fun (and funny) bits of our history. For another, a sanitized history is easily weaponized for bigotry when it declares us better in one way or another than some other populations. But mostly, I just find it tiresome. I am even more tired of hearing the blind adoration of our Anabaptist and Mennonite forbears than I am of hearing them judged in shock and horror by disillusioned Mennonites.

And that says something.

I have no doubt that some Mennos will heed this call for repentance and we can thank Wall for inducting more members into the club of the disenchanted. But there is no easy way to make a wholesale change to how Mennonites view the past. While national governments can conceivably revise the secondary school curriculum to de-mythologize the past, there will never be a Mennonite history course taught in the public school systems. Scholars might write and bloggers might blog but only those Mennonites who really care about history will dig beneath the surface that is presented in Sunday School lessons and around the family dinner table. So I’m not counting on an all-out shift in the Mennonite historical consciousness anytime soon.

I can’t say I care all that much. Disillusioned Mennonites are not, as a rule, any more fun than the Menno-innocents. With all their earnest finger wagging, they’re about as welcome at a cocktail party as a revivalist preacher. Though likelier to accept an invitation and drink heavily there.

As for me, I’m looking forward to a time when we can take ourselves – and our history – a little less seriously. Not in a way that ignores the past but in a way that learns from it. Sometimes the past is our enemy. That means we need to love it.

Disillusioned Befuddler

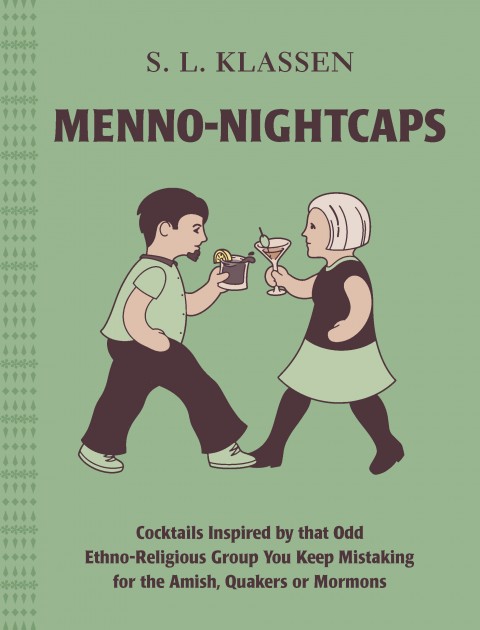

A cocktail with raspberries would have been most appropriate for Gerhard as he devoted himself to raspberry farming after immigrating to Canada. I, however, have chosen to honour Gerhard’s son and all the other disillusioned Mennos out there. This cocktail uses sour cherries.

A cocktail with raspberries would have been most appropriate for Gerhard as he devoted himself to raspberry farming after immigrating to Canada. I, however, have chosen to honour Gerhard’s son and all the other disillusioned Mennos out there. This cocktail uses sour cherries.

Make sure to pick out the sourest from the basket.

- 1 1/2 oz gin

- 1/2 oz maraschino liqueur

- 1/4 oz lemon juice

- dash of orange bitters

- 4-6 oz soda water

- 12 pitted sour cherries + more to garnish

Muddle the cherries in the bottom of a shaker. Add gin, maraschino, lemon juice and ice. Shake. Strain into a glass and top with orange bitters. It is good as a strong cocktail like this but for a tall drink for a summer afternoon, top with soda water and serve on ice.

My love and I have been feasting on A French Village. Or rather, it’s been gnawing on us. It’s about a fictional French village occupied by the German army in the late ’30s and then eventually the SS. Almost every character is compromised, the gradations of evil ranging from colorless little lies to the flamboyance of the Devil’s rainbow. I want to believe Mennonites would have been among the former, myself included. But then, as an American, I asses my current state of fidelity to the Myth, and think it may have more hues than what I want to believe. The Myth nor its past alloyed practitioners are not the locus of my disillusionment, which is why I’ll have that Disillusioned Befuddler now.

Or, one could just stop thinking of Mennonite as a category worth examining either historically, culturally or theologically. There are no rationally compelling reasons for Mennonites to exist as a church or culture in 21st Century North America.

I do find material history of Mennonites interesting, because when you look at the ordinary everyday lives of Mennonites you will find that they arn’t much different from their neighbours. But that just illustrates my point above.

Hi Sherry

I somehow missed this blog entry and knew nothing about Gerhard’s Journey until the middle of last night after an innocent Google search. Do you know anything about the writer? He has done an amazing job as have you with your blog. I appreciate your insights and analyses of the Menno world as befuddled as it is. Many thanks.

Sandy Callahan