For the last few years of his life, my father put his time up on the auction block.

Not the time left in his life as in some kind of Mennonite dystopia where one’s lifespan is determined by the highest bidder at an auction.

Just a half hour or so of his time.

What happened was this: his Church had an annual auction sometime in the spring to raise funds to cover their budgetary shortfall. I don’t know if it was on the same day every year. In 2011, it happened a few weeks after Easter.

Prior to the auction, Church members donated items and services of value. My father contributed “Coffee with Aaron.”

He wondered, the first year that he submitted it, whether anyone would actually bid or whether he would feel, instead, the community’s scorn with his little joke falling flat.

He needn’t have worried.

I don’t know who the Church enlisted as an auctioneer but whoever it was worked that special auctioneering magic and managed to persuade not one but several bidders that a trip to a coffee shop with my father was worth a couple hundred dollars.

Mennonites — we love our auctions.

It took me awhile to understand the appeal of the auction. My parents frequented an auction house in Cambridge when I was young — I thought of it as their version of a date night, though every now and then I went along when a babysitter couldn’t be found. It was held in a dank and smoky building and I appreciated none of the auctioneer’s magic at the time, even if my parents did manage, from time to time, to bring home an unusual chest of drawers or a box of surprises. In my opinion, the surprises were frequently disappointing.

But my parents saw the magic. They loved the thrill of bidding in competition, allowing themselves to be driven up to their limit and then either winning or resigning, content in the knowledge that when they lost, it was because they were steadfast in their conviction to not bid past whatever limit they had set. And being steadfast in one’s convictions is always a virtue worth celebrating. Especially, perhaps, when that steadfastness persisted despite relentless pressure from the auctioneer casting his fast-talking spells.

There were some, I know, who feared the power of the auctioneer. Legend has it that my family lost our ancestral Kroeger Clock when a certain wily Mr. Toews persuaded my great-grandfather to a private sale, thus denying all his grandchildren the opportunity to bid on it at the auction held to dispose of their chattels. My father, being one of those dispossessed grandchildren, resented this loss for years, and, though he recognized the legality of a private sale, still always saw something underhanded in one who sought to circumvent the auctioneer rather than engage with the auctioneer’s particular brand of sorcery.

I am not sure I agree on this assessment but I also came to appreciate the auctioneer’s enchantments.

Once I did come to appreciate them, I, in fact, became so bewitched by the dulcet tones of the auctioneers that I harboured auctioneering as a secret life ambition.

Credit for that goes to the New Hamburg Mennonite Relief Sale and the auctioneers there who are both magicians and superstars.

I went every year throughout my childhood and though there were food tents and craft tents and neverending lineups full of friends and family, at the very centre of it was the auctioneer. He stood and performed his magic right there, in the middle of all the festivities. The auctioneer was the man who, like an alchemist turning lead into gold, instead made cash out of quilts.

I say “he” because the auctioneers I saw were always men back then. Which was part of the reason I never thought I could realize my secret dream and become one of these magicians myself.

But I envied them.

On Mennonite Relief Sale day, they took up their craft and mesmerized an entire auditorium full of skinflint Mennonites and, using nothing but their quick tongues and waving arms, persuaded the Mennos to part with their money.

Which was no small feat, indeed.

And no one feared the auctioneer at the Mennonite Relief Sale. Instead, because the money is all raised for charity, it was as if the bidders were in collusion with the auctioneer, all wanting the prices to soar even as that desire competed with their natural love of a bargain and their covetous desire to take home a beautiful quilt. This meant that virtue could be claimed on winning or losing a quilt. Because if losing meant steadfast resolve, winning meant heightened charity. And charity, we all know, is greater than faith and hope, let alone steadfast resolve and frugality.

Who wouldn’t envy the auctioneer who was at the centre of all this?

They were, as already mentioned, superstars that day. Not like regular, worldly celebrities. They didn’t get followed around and photographed by Mennonite paparazzi; the Mennonite media didn’t write puff pieces on the lives, fashion choices and life philosophies of auctioneers – I don’t think I’ve ever even seen one on the cover of the Canadian Mennonite. There are no Mennonite bubblegum cards for auctioneers.

But they were superstars, nonetheless. Sometimes, when wandering around the food tents with my cousins or friends, one of us would spot an auctioneer who had come off a shift and we would point discreetly and whisper to each other as if we had seen a celebrity. Because we had.

We haven’t had live auctions at the New Hamburg Relief Sale for two years now but in other ways it is much the same, though my cousins and I have grown and might have the confidence now just to smile and nod when we see a celebrity auctioneer in real life.

It’s possible that my parents’ church brought in such a celebrity for their annual spring auction or they might have just run it with amateurs who had picked up a few of the magic tricks.

Whoever it was raised the greatest funds as payment for “coffee with Aaron”when they ran the auction in 2011. I am told that on that particular year, the room went silent for a moment or two and the auctioneer paused after reading the item. This was because my father had passed away suddenly in the weeks between writing up his submission and the date of the auction.

But after the pause, he started in and the bidding began. I wasn’t there but I can well imagine the “ten dolla dolla dolla dolla dolla bill” of the auctioneer’s chant moving swiftly upwards with various congregants using their bids to both honour my Dad’s memory and raise funds for the Church, none of them really knowing how they would actually enjoy that cup of coffee with my deceased father.

My mother didn’t bid at all. She just sat and basked in the experience. Maybe she thought it would have been inappropriate for her to bid on her dead husband’s time, though of everyone there, I have no doubt that she would have appreciated the opportunity the most, were she really able to meet him one more time.

When it was finished, it was decided that the four top bidders would go together to a coffee shop and have a conversation there in honour of my Dad. And that is why my mother ought to have bid. They were always young or middle-aged men who bid on my Dad’s time and it would not have occurred to them to bring an older women with them to a coffee shop outing any more than I, as a child, could imagine myself as an auctioneer. Though perhaps had she entered into the auction, the winning bidders would have considered breaking down the barriers to mixed-gender grieving.

It is possible.

Because entering into an auction always opens up possibilities. It wouldn’t have cured her grief, still so very raw as it was, but I wonder if it would have shaken things up just enough to give her that little bit of balm that she so wanted. Gender norms are, after all, open to change.

Hey, I’ve even heard tell of a female auctioneer appearing at a Mennonite relief sale.

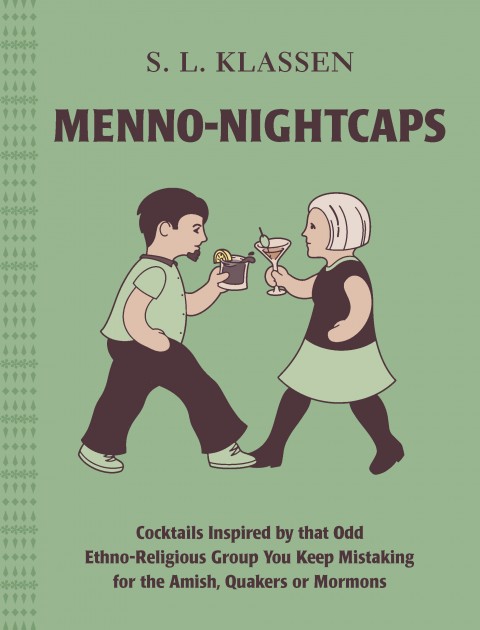

This cocktail is somewhere between a Millionaire cocktail and a fillibuster — which seems fitting given the focus on money and talking.

The Ten Dolla-Dolla-Dolla-Dolla-Dolla Bill Cocktail

- 2 ounces bourbon

- 3/4 ounce Triple Sec or another orange liqueur

- 1/2 ounce lemon juice, freshly squeezed

- 1/2 ounce maple syrup

- 2 dashes star anise bitters (or a dash of absinthe)

Measure bourbon, Triple Sec, lemon juice and maple syrup into a cocktail shaker, filled halfway with ice. Shake vigorously and strain into a coupe or cocktail glass. Add the bitters or absinthe.

Garnish the cocktail with a pretty flower and then raise it high for all to see and start the bidding at $10.

0 Comments