This post was first published in April, 2015. I have made some minor edits, but otherwise kept it the same.

This post was first published in April, 2015. I have made some minor edits, but otherwise kept it the same.

For years – centuries, really – Mennonite women have been doubly silenced. Once by a broad patriarchal society that shut down all women’s voices and then additionally by a religious culture that reinforced that message. We all know this by now. Look at the Mennonite history texts (yes, there are Mennonite history texts) from the first 75-100 years of the twentieth century and it’s hard to find a woman even pictured, let alone named.

In the last couple of decades a few stalwart women have brought some of the lessons of feminism into the arcane halls of Menno-academia so all is not without hope. Still, while we now acknowledge that women did, in fact, live in the Mennonite communities of the past as well as of the present, I get the feeling that we’re not all that sure how to think of them.

Case in point. I recently saw an art exhibit called Along the Road to Freedom: Telling the Story of Mennonite Women of Courage and Faith that pays tribute to a number of the women who showed “courage and faith” when times were tough in Russia. In written and oral statements about the project, the artist, Ray Dirks, says that initially a small group of Russian Mennonites got together and approached him at the Mennonite Heritage Centre in Winnipeg because they wanted a way to memorialize their mothers, grandmothers and aunts. One by one families stepped up and commissioned paintings of their mothers or grandmothers. Dirks listened to stories and gathered photos and then did a series of paintings, each one a collage meant to represent the woman honoured. The exhibit is currently touring.

I expect the families are all happy with the results. Who wouldn’t be? These paintings are all representations of the absolute paragon of Mennonite womanhood. These women suffered due to factors outside of their control but they held onto their faith, forgave their persecutors and went on to be lovely, gentle mothers and grandmothers who served their families and their Church. They appear to have been resourceful without being outspoken, clever without being proud, strong but compassionate. They represent an image of womanhood that pulls together when times are tough but then steps back to sit by comfortably with a lapful of grandchildren afterwards. These are the images of beloved grandmothers, and the production of the art nothing if not a work of love.

I get it. Actually, I get it twice over. These are my people. My grandmother fled Russia after the Russian Revolution and famine, my grandfather rescued a female cousin he found in Germany after the second world war. I heard these stories; I saw the scars. Also, I know what it’s like to memorialize. When my grandmother died, I wrote not one but two tributes; when my father died, I wrote the obit and I was right in there memorializing him, creating a myth out of his life, a meaning that made death and grief a little easier to take. I knew what I was doing, but I did it anyway. Just couldn’t help it.

It’s a human thing to want to memorialize. Nations do it to make the loss of our children at war seem meaningful. They make heroes out of victims and heroic actions out of accidents and tragedies. Coming from a peace church tradition, we mostly know by now that the memorials that our governments feed us are not the whole truth. And we resent the lies even as we feel for the mourning families who cling to the lies inherent in the memorialization. And here, too, I feel for the families. We want to memorialize. We want to keep Oma’s memory alive if only in a painting and, just like the government wants to control the image, we want to see our own dead as heroes. And so I understand and feel some empathy for those families who pooled together their resources to commission a painting as a memorial.

But it’s not just a memorial, is it? It’s presented as an art exhibit. And, as art, it deserves more than our sympathy; it deserves critical engagement. It deserves to be thought about and evaluated in terms of the images it is presenting and impressions it is creating. Such critical engagement might be at odds with the memorial function that offers a salve of comfort to the bereaved but it is the wages of art to face questions that reach further than the balm of nostalgia.

The exhibit is art and, as art, it presents an impression. That’s what art does. But what impression? First, it presents a nice impression. I can’t think of anyone having qualms about hanging a single one of these painting in their living room above the sofa. Which is perhaps a little odd, given the context of oppression, tyranny and war. The paintings are overwhelmingly nice, tinged as they are in sepia nostalgia. Even the troubles that the women endured — that are clearly part of the story here, for how else could these women be courageous if not in the face of adversity — are left vague. Perhaps we are meant to read between the lines to know that rape and starvation followed them where they went. But such imagery would have been unseemly. It would change the whole tone and some things might be better left unimagined if we want to retain our image of Oma sitting under the Linden tree schnitzing apples. In fact the most explicit suffering that any of them suffered was the loss of a husband. This, it appears, is worth speaking of. I’m sure their grief was real and appreciate that. Again, I am not without sympathy.

But here we have the paradox that the women are both universal ideals of womanhood and exceptional since they were forced, almost unnaturally, to exist without male protection and we are amazed that they survived and for the most part kept their children alive as well. One of the painting’s captions even said “She appeared to be an ordinary Mennonite woman but she was actually very strong.” How’s that for a backhanded compliment to Mennonite women everywhere?

Next, the overwhelming impression is one of sameness. Though the paintings have different subjects, they are stylistically identical with similar tones and composition. How different it would be if they had chosen different artists for each piece and allowed the series to be e celebration of diversity instead of a visual statement of universality. Perhaps they might even have found a female artist for one or two of them. We know implicitly that the women were not chosen to be representative; they were really what we might call a convenience sample of women whose families had the funds to commission a portrait and wanted a memorial. But this is only implicit and, instead, the written materials go out of their way to point to the inclusivity of their project in that they included women with different migration patterns and even one who remained behind. Well, that’s one kind of inclusivity.

So, what are we left with when we leave the exhibit? A lovely image of a smattering of women, all embodying traits with which we’re all pretty comfortable. The design of the project may have shaped that. After all, the embittered, broken women who embarrassed their children with crude language and Nazi sympathies may not have had family members who felt like coming forward and commissioning a painting.

Because, you know what? They didn’t all just up and forgive their rapists and they didn’t all just emerge unscathed from the traumas of their youth. But go ahead. Look at the paintings. Enjoy the nostalgia. Marvel at the courage and the faith portrayed there. That’s what remembrance is all about. And if it isn’t the whole truth, and if it reinscribes the very patriarchal ideals that oppressed the women we are honouring, well then so what? It’s all too much to take in, the contradictions of the past, the ugliness that resides beside beauty.

Let’s not think too much about that before having a drink. It’s easier just to remember the courage and the unending faith.

Courage and Faith

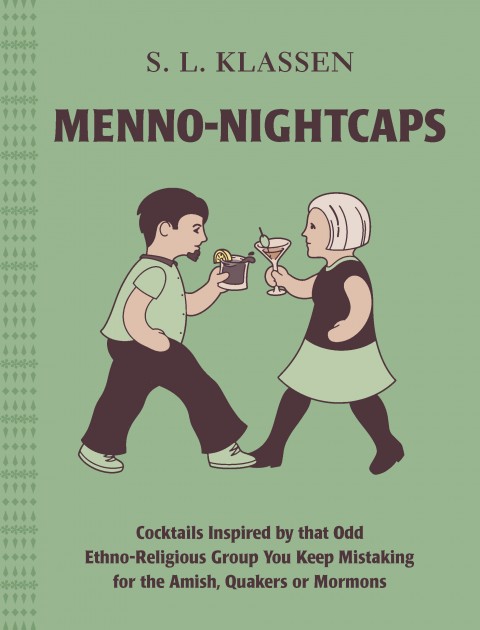

This cocktail combines the citrus Genever tastes of Dutch courage with the jalapeno spice of the Leap of Faith cocktail. Sounds like Courage and Faith to me.

1 oz genever gin

1/2 oz grand marnier or other orange liqueur

1/2 oz amaretto

1/2 oz orange juice

1 very small piece of jalapeno pepper

1. pour all of the ingredients into a shaker half-filled with ice.

2. shake vigorously

3. strain the cocktail into a glass with more ice, discarding the jalapeno pepper

4. sip carefully and let the jalapeno burn remind you of all those things you would rather forget.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks